How Much Money Do Refugees Get

W idad Madrati remembers the first snowfall at Oreokastro in the way most children would, as a thing of wonder. It threw a brilliant white cover over the squalor of a refugee camp pitched in the grounds of a disused warehouse in the hills above Greece's second city, Thessaloniki. The 17-year-old Syrian did not mind that the water pipe to the outdoor sinks had frozen. She took photographs of the icicles.

The pictures on her phone show nothing of the broken chemical toilets or the discarded, inedible food; nor of the flimsy tents pitched on freezing ground by refugees, such as her family, who arrived too late to find a spot inside the concrete shell of the old warehouse. Instead, the images show children playing in the snow.

Stranded outside the Oreokastro buildings, in a tent dusted with white flakes, the other members of the Madrati family were more realistic about survival and begged the authorities and volunteers for a way out of the camp. A family of four when they left Aleppo, they became five along the way – Widad's sister Maria was born in Turkey – and had endured worse indignities in Greece than pleading.

The family was among the last to leave their previous temporary home at Idomeni, close to the border with Macedonia, on the overland western Balkan route to northern Europe. They held on in the chaotic encampment for 10 weeks after Greece's northern border closed in March 2016, in the hope that it would reopen. It did not. The settlement was evacuated and its residents moved to former industrial sites such as Oreokastro and disused army barracks. "I was crying when we left Idomeni," says Widad. "I felt I was losing hope after so many people had crossed the border and we could not."

She tells her story in the English she learned from volunteers at Idomeni and then taught to other refugee children at Oreokastro. Her family, who qualify by almost any criteria as refugees, have witnessed much of what has gone wrong in Greece since the country became the gateway to Europe for record numbers of refugees and migrants.

From their arrival at Moria on Lesbos, to Idomeni and Oreokastro, the Madratis' route since arriving in the EU has been a tour of previously obscure places in Greece that have gained international notoriety for the misery of their conditions. Their ordeal stands in stark contrast to the international funding and energy expended to help people like them.

A sequence of events beginning with the record number of people who flowed into Greece in June 2015 and culminating in the photograph of drowned Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi woke the world to the refugee crisis. The effect of that awakening was to tip the entire humanitarian complex toward Greece, sending resources tumbling out of the developing world into the European Union. It prompted an unprecedented number of international volunteers to descend on the country, the UN refugee agency to declare an emergency inside the European Union, and the EU to deploy its own humanitarian response unit inside Europe for the first time. In the process, it became the most expensive humanitarian response in history, according to several aid experts, when measured by the cost per beneficiary.

Exactly how much money has been spent in Greece by the European Union is much reported but little understood. The online media project Refugees Deeply has calculated that $803m has come into Greece since 2015, which includes all the funds actually allocated or spent, all significant bilateral funding and major private donations.

The biggest pots of money are controlled by the European Commission (EC), the EU's executive body, which oversees the Asylum Migration Integration Fund (AMIF) and the Internal Security Fund (ISF) which collectively dedicated $541m to fund Greece's costs related to border control, asylum and refugee protection. However, since it did not complete the extensive strategic planning required, the Greek government did not receive significant amounts of these funds, necessitating emergency assistance from the commission, channelled through other means. Confusion over the true extent of European spending has been exacerbated by inflated statements from the European commissioner for migration, home affairs and citizenship, Dimitris Avramopoulos, who has regularly cited figures in excess of €1bn, although this amount apparently refers to all available and theoretical funds, not what has actually been allocated or spent.

Nevertheless, the $803m total represents the most expensive humanitarian response in history. On the basis that the money was spent on responding to the needs of all 1.03 million people who have entered Greece since 2015, the cost per beneficiary would be $780 per refugee. However, the bulk of these funds was used to address the needs of at least 57,000 people stranded in Greece after the closure of the borders on 9 March 2016, and on this basis the cost per beneficiary is $14,088.

Officials from the EU's humanitarian operations directorate, Echo, believe the payout per beneficiary was higher than any of their previous operations. One senior aid official estimated that as much as $70 out of every $100 spent had been wasted.

The haunting image of Alan Kurdi, lying drowned on a Turkish beach on 2 September 2015, was shared more than 20 million times on social media. It prompted an immediate spike in Google searches related to Syria and an avalanche of private donations to charities working on behalf of refugees.

The Swedish Red Cross saw its daily donations leap 55-fold in the week after the image circulated, according to a study led by Paul Slovic at the University of Oregon. At the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a New York-based relief group, response to the photograph crashed its website and drove a surge of public donations. Slovic says that Kurdi's death "woke the world for a brief time". It also made it imperative for international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) to show they were responding to events in the eastern Mediterranean.

For the established groups already working in Greece, the sudden influx of funds was both welcome and destabilising. Metadrasi, a Greek organisation known for training interpreters and caring for unaccompanied minors, had experienced staff poached by bigger new arrivals on the scene that could afford far higher salaries.

The head of Metadrasi, Lora Pappa, believes the tide of money transformed refugees into "commodities" and encouraged short-term responses. "They [international organisations] were looking at how to show a presence in Greece. This led to some wasting the chance to spend constructively."

Her rueful conclusion is that "sometimes money can do more harm than good".

Among the cautionary tales to emerge from this period was the Apanemo transit centre on Lesbos. A million-dollar facility built by the IRC on the steep hillside close to the main landing beaches during the busiest months in 2015, it was designed to receive 2,000 refugee arrivals per day. Funded by private donations, British aid money and the charitable Radcliffe Foundation, it was hailed by the IRC as a "much-needed reception centre [that] provides crucial services to refugees".

Apanemo never ran at anything approaching capacity – partly because the refugees started landing on a different part of the island – and was mothballed in March 2016. The IRC says it has been able to dismantle materials and use them at other facilities, but the site now stands empty, while chaotic conditions elsewhere on the same island have resulted in fatalities among refugees. But the rapid deployment of resources with questionable results was in no way confined to the IRC.

The decision by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) to classify the situation in Greece as an emergency turned what had been a backwater posting into a major placement almost overnight. An office with a dozen staff who had previously spent much of their time overseeing contract workers assisting the Greek asylum service expanded rapidly. The UNHCR team in Greece expanded to 600 people across 12 offices. Roughly one-third of the workforce were international staff.

International UNHCR staff earn three times more than their local counterparts. Fotini Rantsiou, a Greek UN staff member who took a sabbatical from the organisation to volunteer, says tensions between local and international staff complicated relations within the agency. She says local staff were sidelined and "treated like secretaries" by the newly arrived international staff.

The decision to take a role in the Greek crisis also put the UNHCR on a collision course with one of the core elements of its mandate: to advocate for the rights of refugees. Operating for the first time on this scale inside the EU, which is also the organisation's second biggest funder globally, the UNHCR faced a dilemma over criticising its donors. "Instead of advocating for the protection of refugees they remained silent for fear of the political consequences," says Rantsiou. "Even if they wanted to criticise policy that violates their principles, they could not."

The international organisations would work with a Greek administration that, at least in terms of its public statements, was among the most refugee-friendly in Europe. However, problems arose because many officials from the ruling Syriza party were inclined to see the well-financed foreign organisations more as colonialists than as humanitarians.

One senior Greek official says that he detected "a colonial mentality" among some aid workers who received hardship pay while working in the relatively comfortable environment of Greece: "It was a good job to work in a country with fine restaurants and comfortable beds and be paid like you were in Somalia."

The resentment was fuelled by the fact that much of the funding on offer was directed via international aid agencies, not the Greek government. This was ultimately damaging, according to diplomats, Greek officials and aid workers, since the government had the role of coordinator and had final sign-off on projects. "Coordination of the response has been a key obstacle, with the UNHCR failing to work productively with the government and the government failing to make urgent, strategic decisions quickly enough," said the UK-based charity Oxfam in a statement.

Mass migration is not something new to Greece. An influx of migrants from the Balkans and farther east arrived from the 1990s onwards and were largely left to fend for themselves. The most the issue merited was its own section at the Greek Ministry of the Interior. But in the last couple of years Greek migration officials have had access to one of the largest money pots administered by the European Commission, the aforementioned AMIF and ISF funds.

These funds are relatively complicated to access. They are arranged in seven-year programmes, commencing in 2014, and required Greece to set up a managing authority and develop a strategic plan. When Syriza took office it found little of this groundwork had been done by the previous conservative administration. The government, preoccupied with resolving its debt crisis, showed equally little interest in taking the first steps to access these funds. European Commission officials complained they could find no one to talk to in Athens, despite having half a billion euros potentially on offer.

It took the historic wave of refugees and migrant arrivals that crashed over the Greek islands in June 2015 to force a rethink. Some early steps were taken to establish a managing authority and submit a plan. But after a cabinet reshuffle and fresh elections these efforts were put on hold.

The reshuffle brought Ioannis Mouzalas into the role of junior minister. An obstetrician with lengthy service at the medical charity Doctors of the World, he appeared a strong choice for the role. But those hoping for a step change would be disappointed. A ministry official involved in setting up the managing authority to access European funds told the new boss that the technical preparation was important. It was explained to Mouzalas that the ministry needed to devote "a significant portion of our time to the managing authority" in order to get "a system that works".

As the autumn of 2015 approached, Greece remained a refugee corridor, with the majority of new arrivals spending less than a week after arriving on the islands before their exit over the northern border along the western Balkans route. As hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants passed through Greece, it became obvious the country had no mechanism to compel new arrivals to apply for asylum.

Greece came under considerable pressure from the EU to set up reception centres on the eastern Aegean islands of Lesbos, Kos, Leros, Chios and Samos, in order to identify and fingerprint all new arrivals. In October, the Greek prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, promised the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, that the reception centres would be operational within a month.

In late October 2015, regional leaders converged on Brussels for a meeting to discuss the western Balkans route in an atmosphere described by one diplomat present as "scarcely concealed panic".

It was already clear to the gathered leaders that any future plans to stem migrant flows into Europe would be contingent on Greece being able to process new arrivals, identify those in need of protection, and deport those deemed not to qualify. It was also clear to everyone that Greece was nowhere close to being able to do these things.

"Either you massively help [Greece] now or you'll face a huge number of migrants entering the EU," a senior UN official told the European Commission. On the sidelines of the meeting, Frans Timmermans, a vice president of the EC, admitted to the UN refugee agency that the Commission had "no idea" how to deal with the situation.

By the end of the meeting, Greece had been offered emergency funds to accommodate a total of 50,000 refugees, with the UNHCR tasked with finding places for 20,000 of these in hotels or apartments, and the remainder to be housed in camps under Greek authority.

By mid-November it was already clear that diplomatic agreements were not changing the situation on the ground. An EC team that conducted spot checks in Evros in northern Greece and on the islands of Chios and Samos reported that "nothing seems to be prepared or planned … The whole system seems to be organised to register migrants and let them leave."

A Greek policeman serving at the Moria camp put it more succinctly when explaining that his job was to get a copy of an ID and a fingerprint, and then speed new arrivals on their way to Germany: "Copy, finger, Merkel."

After the autumn of 2015, a Friday ritual was established. In Athens, representatives of the Greek army, police and several ministries would meet with a team from the European Commission and the UN to update them on progress. But on the second Friday of February 2016, this comfortable routine was disturbed by Maarten Verwey, the EC's special envoy who broke the news that the border was closing. "Guys, we gave you time," he told the meeting, according to someone present. "You didn't prepare. Good luck. Now it's going to happen."

With his borders set to close, no functioning processing centres and the prospect of a grilling at a European leaders' summit at the end of February, Alexis Tsipras found an unlikely saviour. Panos Kammenos has been one of the indisputable political winners from the upheaval in Greek politics.

Kammenos, a rightwinger, had been persuaded to support the leftwing government, and was rewarded with the defence ministry. Kammenos's contribution to the refugee crisis had been to growl that Europe should back down in debt negotiations or Greece would flood the EU with migrants. When $74m was added to the annual defence ministry budget for refugee support, he saw to it that the Greek army established spartan but functional facilities where they were most needed.

With responsibility for dealing with refugees now divided between several Greek ministries and the UN, EC cash flowed and effective oversight of spending was removed. A series of amendments that passed through the Greek parliament stripped out auditing requirements on contracts related to the refugee crisis.

On 9 March 2016, the migrant trail was halted when the border with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia was closed. Nine days later it emerged that a deal had been agreed between the EU and Turkey, under which Greece would return newly arrived refugees and migrants, and Turkey would stem the flow of people to Europe in return for aid money and political concessions. While this was publicly received as a shock, the government in Athens had known for months what was coming.

It is a popular lament in Greece that the country has good laws but terrible governance. Another good law, law 4375/2016, was added to the statute books in April. It took the ad hoc jumble of different services across different ministries and created a single ministry of migration.

Odysseas Voudouris was appointed by the prime minister to head a new general secretariat, under Mouzalas, which would do much of the groundwork, from running documentation centres to appointing camp directors. The two men had much in common: both were doctors and veterans of medical charities, in Voudouris's case Médecins sans Frontières.

When Mouzalas asked the new official to hold back before taking any initiatives, Voudouris initially agreed. When, six weeks later, he was still watching from the sidelines, he wrote to Mouzalas to tell him the situation could not continue.

The pair stopped speaking to each other, according to ministry officials, and started communicating by letter. Voudouris claimed that instead of a professional bureaucracy with transparent roles, Mouzalas operated an inefficient system staffed by people who lacked relevant experience. Mouzalas declined to comment for this article.

Things came to a head when Voudouris arranged, with the help of the UNHCR and using $1.8m in European money, to recruit 118 contract workers to begin staffing his secretariat. In an exchange of letters, the move was blocked by Mouzalas even after a senior UN official intervened to explain that the hires would be paid for by funds that would be lost if left untapped.

Nikos Xydakis, who worked closely with Mouzalas throughout this period as a junior foreign minister, became increasingly concerned with how the crisis was being handled. He formed the view that there was "managerial negligence. The problems could have been addressed and we could have had a much better situation … Greece can innovate solutions. Now there is no time left for managerial negligence and short-termism."

Speaking to state television in November 2016, Mouzalas deflected responsibility from his ministry. "It wasn't our choice for the money to go to NGOs … this was Europe's decision," he said. "We are not the ones in control of this money. It is controlled by the relevant European authorities; this is the law."

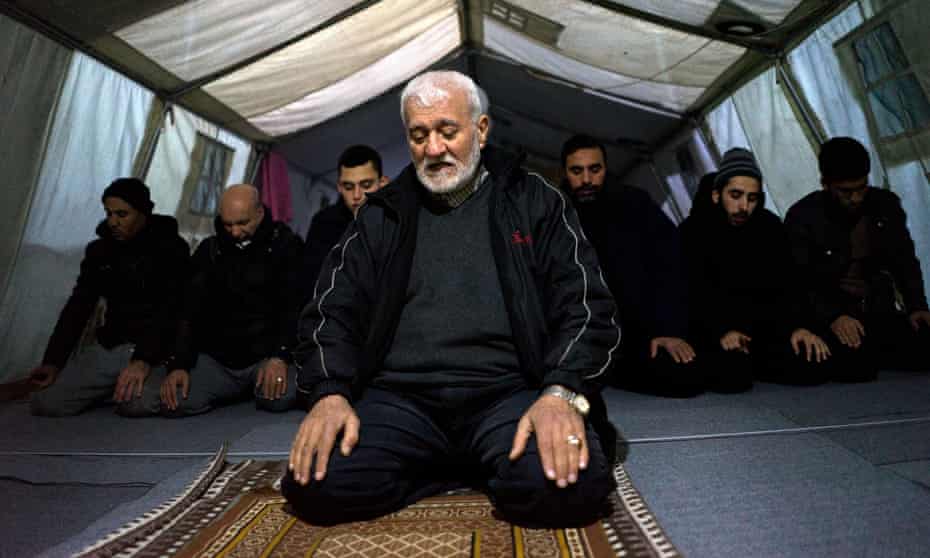

When Imam Ali arrived at Softex, a ruined toilet paper factory downwind of an oil refinery and outside Thessaloniki in April, he slept rough outside the derelict main building. Nine months later, and still awaiting news on whether he could be reunited with his wife in the Netherlands, the 68-year-old Palestinian, who had lived in Syria, was finally moved to a weatherproof container.

The retired engineer picked up the honorary title of imam after leading prayers in a tent that residents use as a mosque. He also led a number of protests over conditions at the camp. When he was eventually granted an audience with UN officials the main thing he wanted to know was: "Who is the leader here at this camp? The police? The army? The UN? Who do we talk to?"

The imam's experience of harsh conditions, helplessness and not knowing who to talk to was common to countless refugees. Forced to warehouse people who were determined to leave, the Greek government pursued an unlikely strategy. An archipelago of camps was spread across the country from a barren hillside above Greece's biggest oil refinery, to the remote villages in the Pindus mountains of north-east Greece and a clutch of polluted and unsafe former industrial sites around Thessaloniki. Owing to heavy metal contamination of the water, exposed asbestos panelling and the presence of mosquitoes that can transmit malaria, the Greek Centre for Disease Control and Prevention recommended their closure in July.

The archipelago strategy placed an administrative and cost burden that the misfiring alliance of the Greek government and international organisations could not sustain. It also revealed the shocking absence of a functioning chain of command.

No one is certain exactly how many refugee camps there are in Greece. Migration ministry bulletins list 39 camps, some of which are empty. Some are closed and others are in the planning phase, but do not appear on the list. The UNHCR said there were more than 50, but did not give a specific number. The ministry declined to comment for this article.

Among the most problematic sites chosen by Mouzalas and his team was a number of privately owned warehouses including Oreokastro, where the Madrati family found themselves, the Karamanlis tannery outside Thessaloniki, and Softex. These sites lacked the basic utilities for large numbers of people.

One of the few blessings that asylum seekers did receive on arriving in Greece late in 2015 was the unusually mild weather. It is a myth that Greece has no winter – temperatures in the north can be harsh from December through February.

By late spring 2016, the larger international aid agencies were already tabling plans to winterise the tented camps and donors were allocating funds. The Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund (ASB), a German NGO, put forward a $1.6m proposal to turn Softex into a 1,500-person site with accommodation in containers, equipped with heating and plumbing. Bilateral aid money from Germany was agreed to fund the winterised camp and the proposal went to the Greek migration ministry.

Instead of signing off and allowing work to begin, the ministry returned with its own proposal costed at $8m. When donors and aid agencies replied that this was a non-starter, Mouzalas refused to budge or negotiate a compromise. In a letter dated 7 July, the ministry wrote to ASB "that for Softex camp our plans will not change". The proposal was rejected.

The fallout from the Softex standoff made it to the Greek parliament later that month: 10 MPs demanded to know how the ASB proposal had been evaluated and why it had been rejected.

Meanwhile, senior officials at the UN refugee agency were receiving late-night calls from Greek ministers demanding resources, which they duly handed over, still with no sense of a plan or any proper record keeping.

"Every time the government would take it right to the edge of the cliff before agreeing to anything," says a European official familiar with the negotiations. "With the winterisation they went right over the edge."

Adding to the uncertainty was a murky game over the number of refugees within Greek borders. After the closure of the northern frontier and the implementation of the Greece-Turkey deal, arrivals slowed dramatically. When the first official count of asylum seekers remaining in Greece was released by the migration ministry, it stated that there were 57,000 on the mainland and the islands.

This number grew, with the trickle of new arrivals on the islands, to 63,000 on the official bulletin from the migration ministry. But the numbers ran counter to what European officials and NGO staff were seeing in the camps, which more and more people were leaving. At the end of July a new column appeared on the ministry report listing "refugees outside camps." As the numbers reported in individual camps fell, the number in the new column rose.

Spot-checks at camps near Thessaloniki carried out by a foreign diplomat found huge discrepancies between the official numbers and those actually present. At Oreokastro, where the official headcount was 604, there were only 135 people present. The caterers at the camp, who receive a budget of $6 per person per day – as they do at camps across the country – were well aware of the discrepancy and told the diplomat they were delivering 200 meals while continuing to receive funding based on the official figures of 600.

When the Wall Street Journal reported in December that thousands of refugees counted in the official numbers were "missing", the ministry responded that the claim was "baseless". It was not until February that the UNHCR finally admitted that it had counted 13,000 fewer refugees than the Greek government. While it is under pressure to show it has its borders under control, Greece can not admit that thousands of refugees have been smuggled into the Balkans. The migration ministry maintains that there are more than 62,000 refugees in Greece.

On 5 January, Mouzalas tempted fate during a visit to select camps in the north by declaring the winterisation complete. "There are no longer any refugees or migrants in the cold," he told reporters. Within days, a new cold snap was accompanied by photographs of refugees in appalling conditions, this time on the islands. Asked about cold-weather provisions, Mouzalas was defensive, saying his previous comments referred to the mainland only and that the tents may not be "four-star accommodation" but they were adequate.

Before the end of the month three asylum seekers in Moria camp on Lesbos died. Footage from the camp made it plain that some refugees and migrants were still in flimsy tents with no protection from freezing temperatures. Local witnesses suggested that the three young men died after inhaling fumes from the plastic they had scavenged and burned in a vain attempt to keep warm. Greek authorities have not yet confirmed the cause of their deaths.

While attention focused on the remaining people in tents in the snow, a costly and desperate face-saving exercise was under way in northern Greece: transferring hundreds of refugees and migrants into seafront hotels and luxury ski chalets in the mountains above Grevena, a three-hour drive outside the city. Entire budgets meant for the development of semi-permanent camp facilities were spent on hotel bills. Aid officials confirm that temporary arrangements with hotel owners will expire this month.

One bewildered Syrian, moved from the squalor of Oreokastro, where tents were pitched in and around the concrete shell of a disused factory, found himself transported into the snowbound Vasilitsa Spa Resort, a hotel with tennis courts and fireplaces, next to a popular ski centre.

"We've been upgraded to this place," he wrote on Facebook. "It's like a refrigerator."

Katerina Poutou has become an accomplished letter writer. A veteran of Greece's suddenly crowded humanitarian field, she is the head of Arsis, one of its largest NGOs. She has waged a battle by correspondence since July 2016 with a succession of Greek ministers in a forlorn effort to secure the basic needs of 600 of the most vulnerable refugees in the country, including unaccompanied minors and lone mothers with children.

The 600 are housed in shelters run by Arsis and seven other groups that clearly qualify for AMIF funds from the European Commission that should be channelled through the Greek government. She has been forced to repeatedly beseech ministries who have been unwilling or unable to work the bureaucratic levers to ensure the necessary funds arrive.

The new ministry of migration, set up by the April 2016 law, was supposed to take over shelter needs for extremely vulnerable groups. Yet the failure of the ministries of migration and development to establish an effective managing authority and access the European funds left those taking care of vulnerable refugees in a desperate situation.

"I am not sure officials understand the consequences of the situation they have created or the humiliation this brings on the country," says Poutou. "I have no idea why they don't make the managing authority function. Any minister who understands the responsibilities of his mandate could have managed this if he was interested."

The situation exploded in February when Greek asylum service workers on the islands went on strike. An asylum service email on 25 January had informed the workers that "timely payments of wages was postponed indefinitely". Since the beginning of the year, the responsibility for paying them had been shifted by law to the migration ministry, but the bureaucracy did not exist to handle it. Seven months after law 4375/2016 passed there was still no clear plan for what it should look like.

Some 40 MPs from the minister's own party have threatened to raise the matter in parliament but for now the minister continues to enjoy the support of the prime minister. His supporters also extend far beyond Athens.

All the minister's public statements declare unequivocal support for the EU-Turkey deal. This staunch backing for the European Commission's key priority of slowing migration has so far shielded Mouzalas and other government figures from any serious criticism.

Some critics see an even more cynical quid pro quo. The bigger the mess in Greece, the harsher the conditions, the greater the deterrent for other refugees and migrants who see the country as a route into the EU, they argue. The lavish European funding – which has been systematically overstated by the migration commissioner – offers plausible deniability of responsibility for conditions in Greece without relieving the very real problems on the ground. A spokesperson for the Commission denied that there was a deterrence strategy, insisting that it was "committed to improving conditions in Greece".

As a Greek living and working in Paris, Dimitris Christopoulos, who heads the International Federation of Human Rights, one of the world's oldest rights groups, has seen both sides of the issue up close. He believes the Greek government has used the mess to shield itself from the possible mass return of failed asylum seekers from elsewhere in the EU. The EC and a number of member states are keen to reinstate the Dublin Regulation, under which asylum seekers can be sent back to the country through which they first entered Europe. Christopoulos is also clear that far from weakening Mouzalas's position with Brussels, the suffering and waste in Greece won him the "absolute support of the commission".

"The Greek administrative chaos is the best deterrence," to others hoping to reach Europe, says Christopoulos. "It sends the message that Greece is a mess so don't come this way."

This article is adapted from a piece that first ran on Refugees Deeply

How Much Money Do Refugees Get

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/09/how-greece-fumbled-refugee-crisis

Posted by: caudillmilatichated58.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Much Money Do Refugees Get"

Post a Comment